Maintain a healthy work environment

Since COVID-19 may be spread by those with no symptoms, businesses and employers should evaluate and institute controls according to the hierarchy of controls to protect their employees and members of the general public.

Consider improving the engineering controls using the building ventilation system. This may include some or all of the following activities:

- Increase ventilation rates.

- Ensure ventilation systems operate properly and provide acceptable indoor air quality for the current occupancy level for each space.

- Increase outdoor air ventilation, using caution in highly polluted areas. With a lower occupancy level in the building, this increases the effective dilution ventilation per person.

- Disable demand-controlled ventilation (DCV).

- Further open minimum outdoor air dampers (as high as 100%) to reduce or eliminate recirculation. In mild weather, this will not affect thermal comfort or humidity. However, this may be difficult to do in cold or hot weather.

- Improve central air filtration to the MERV-13 or the highest compatible with the filter rack, and seal edges of the filter to limit bypass.

- Check filters to ensure they are within service life and appropriately installed.

- Keep systems running longer hours, 24/7 if possible, to enhance air exchanges in the building space.

Note: Some of the above recommendations are based on the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) Guidance for Building Operations During the COVID-19 Pandemicexternal icon. Review these ASHRAE guidelines for further information on ventilation recommendations.

Sick Building Syndrome (SBS)

‘Sick Building Syndrome’ (SBS) is a term that has been used over recent decades. It is used to describe a range of non-specific illnesses that are experienced by an occupant while inside a particular building or within a specific area of the inside environment. The symptoms experienced usually disappear hours, or in some cases days, after the occupant is away from the enclosed environment.

Extensive research has been carried out over recent years to determine the exact science behind the syndrome, and many leading authorities, such as the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Building Research Establishment (BRE) and National Health Service (NHS), have addressed this issue, although it has not been directly referred to under legislation.

The syndrome has received a degree of publicity, with Prince Charles specifically commenting on SBS and blaming it, along with poor urban planning, on contributing to social and health problems. It was reported that the Prince of Wales told delegates at a London environment conference that

We are beginning to see that when we build badly, it doesn't only affect the health of the natural environment, it affects our own health as well. (Building Magazine, 2005)

Despite this media coverage, the syndrome's existence is still unknown in many workplaces. Many employers may be unaware of its existence, and furthermore, of what can be done to help remedy it.

WHAT IS SICK BUILDING SYNDROME?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines SBS as follows:

Sick building syndrome n. a syndrome of uncertain aetiology consisting of non-specific, mild upper respiratory symptoms (stuffy nose, itchy eyes, sore throat), headache and fatigue, experienced by occupants of ‘sick buildings’; (also) the environmental conditions existing in such a building; abbreviated SBS . (Oxford English Dictionary (OED), 1989)

Further to this, SBS is a term that has been assigned to a number of ailments that people experience while occupying a building that then disappear hours or days after the person leaves the building.

SBS relates to non-specific illnesses, and an HSE report states that it can be ‘discriminated from other building-related problems such as physical discomfort, infections and long-term cumulative chemical hazards such as asbestos and radon’ (HSE, 1992).

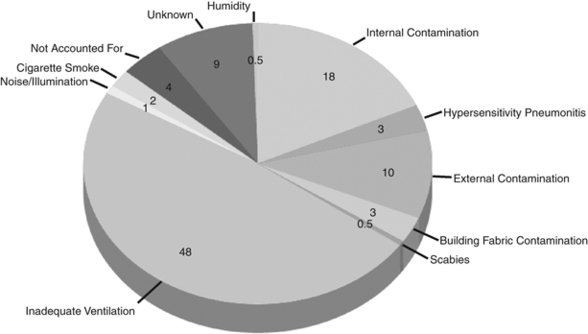

Poor ventilation rates and ineffective circulation of air is held as the main cause of Sick Building Syndrome. Air conditioning units and the pollution within the atmosphere from both inside and outside the building are believed to be the main contributors. This pollution is then circulated around the build, which has a negative effect on the Indoor Air Quality (IAQ), because of high numbers of air contaminants such as gases like CO, CO2, VOCs and particulates.

Motivating this theory is the fact that when ‘energy efficient’ offices were constructed from 1973 onwards, the amount of outdoor ventilation per individual occupant was set at five cubic feet per minute (cfm). This amount was considered in many cases to be highly inadequate for maintaining a healthy and comfortable working environment. It was not until the mid-1990s that the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) revised the amount per occupant to 15 cfm, this being raised to 20 cfm for offices and up to 60 cfm (minimum) for areas of specific use where heavy pollution may accumulate, or is produced (Bialous and Glantz, 2002).

This additional ventilation rate may help to reduce the number of complaints regarding indoor air quality, and this has not yet been proven, although the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers states that

… SBS is not linked to the type of ventilation or air conditioning system used but is more likely to be a function of how well systems are installed, managed and operated … Workspaces conforming to CIBSE guidelines on temperature and air movement should not suffer SBS, unless there are aggravating work related factors or extreme levels of pollution. (Armstrong, 2001)

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

VOCs are carbon-based (organic) compounds that have a high vapour and low water solubility, and therefore evaporate at ambient temperatures within a building. These compounds come from a range of indoor sources such as photocopiers, printers and cleaning supplies.

VOCs cause damage to the human body in a variety of ways, ranging from headaches and fatigue to shortness of breath, when exposed to significant levels.

Experts estimate that the VOC levels of indoor air sometimes reach 100 times those of outside air (All Business, 1990).